Since I first started out in ophthalmology, treatment for glaucoma has focussed on reducing intra-ocular pressure (IOP). Glaucoma, often referred to as the “silent thief of sight,” is a progressive eye disease that damages the optic nerve and can lead to irreversible vision loss. Elevated IOP is the most important risk factor, but many patients with glaucoma have IOP in the “normal” range, and although lowering IOP makes a big difference to most people, and preserves vision for many, it doesn’t restore vision and doesn’t salvage vision for everyone. The quest for other therapeutic strategies has been an epic, but so far disappointing, enterprise. Interventions that can protect (neuroprotection) or help regenerate (neuroregenration) the delicate retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and their axons, the retinal nerve fibres that form the optic nerve, remain a Holy Grail.

Recent advancements have provided a glimmer of hope for patients living with glaucoma.

One such promising avenue of research involves the use of neurotrophic factors – specialized proteins that support the growth and survival of nerve cells in the eye. Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor (CNTF) stimulates the regeneration of RGCs and photoreceptors (the cells in the retina that respond to light and underpin vision). An implant (NT-501) with genetically-modified cells that express CNTF is currently undergoing evaluation in a Phase 2 trial that is due to finish up this year. Recombinant human nerve growth factor (NGF) is also being evaluated, administered as an eye drop. The Phase 1 study of 60 patients was reported in 2022 and showed good tolerability but so far no impact on glaucoma.

Dietary supplementation with Nicotinamide has shown promise. Nicotinamide is required for the production of NAD+, essential for mitochondria, which act as a cell’s power station. RGCs use a lot of energy, and healthy mitochondrial function is essential. A recent Phase 2 study showed some improvement in visual fields in patients taking nicotinamide and pyruvate supplements.

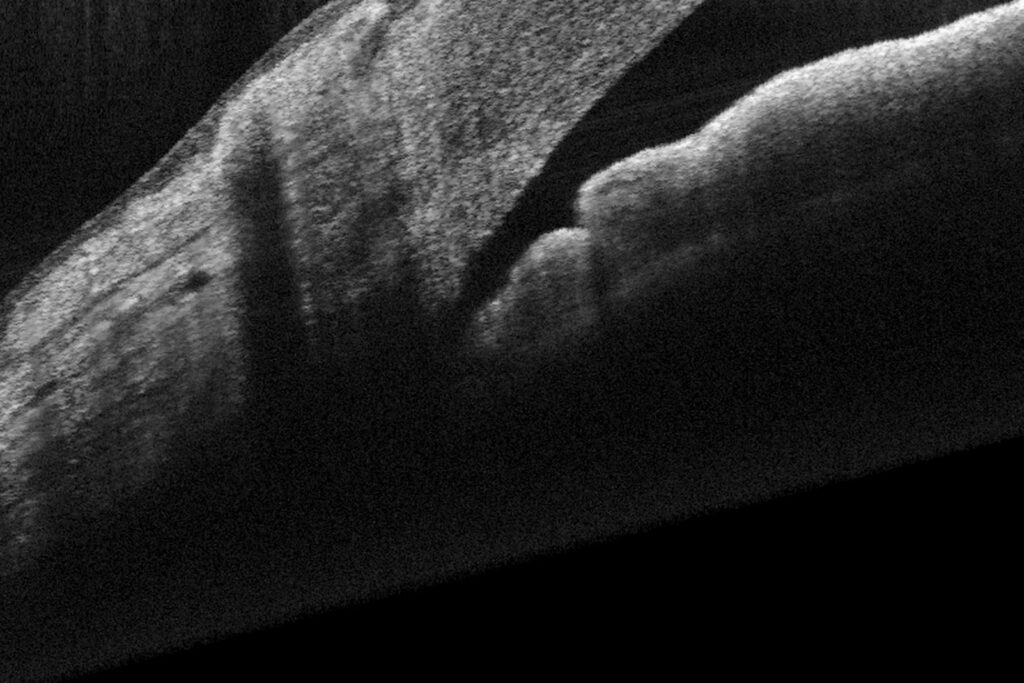

Advances in imaging techniques have allowed for more precise monitoring of the structural changes associated with glaucoma. High-resolution optical coherence tomography (OCT), for example, provides detailed insights into the integrity of the optic nerve and can help us tailor treatment plans to individual patients. Glaucoma management is becoming both more personalised and more proactive.

Challenges remain in the quest for effective support of RGCs in glaucoma, but recent progress in research and clinical practice offer hope for patients facing this sight-threatening disease. By continuing to explore innovative therapeutic approaches and individualized treatment strategies, we move closer to a future with more effective vision preservation.

Beykin G, Stell L, Halim MS, et al. Phase 1b randomized controlled study of short course topical recombinant human nerve growth factor (rhNGF) for neuroenhancement in glaucoma: safety, tolerability, and efficacy measure outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 2022; 234:223–234.

De Moraes CG, John SWM, Williams PA, et al. Nicotinamide and pyruvate for neuroenhancement in open-angle glaucoma: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2022; 140:11–18.